Cadence Testing Brighton Marathon

Way, way back many centuries ago… 2013 actually, I used attendees of the Brighton Marathon Expo (for whom we were the offical Physio & Sports Therapists at the time) to challenge the all too common misassumption that the optimum cadence for runners was 180spm (steps per minute). The results proved interesting!

In my article Heel Striking, Root Of All Evil, we saw that the common belief that all good runners should be landing on their toes is actually a myth. According to studies, the clear majority of runners in a marathon land on their heel (88% at the 6 mile mark and 93% by the 20 mile mark), so unless all of them are doing it wrong it would seem that for the majority of us a heel strike is the best way to run marathon!

The all important factor is not the part of the foot that lands, but rather how straight the knee is at initial impact. Overstriding is where at initial contact the front foot is noticeably far out in front of the body, and indeed some research suggests a locked out knee can create excessive braking forces on that knee.

Runners who overstride at a given speed tend to take less steps per minute, i.e. have a lower cadence. Research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison investigating the relationship of impact forces and cadence concludes that “subtle increases in step rate can substantially reduce the loading to the hip and knee joints during running and may prove beneficial in the prevention and treatment of common running-related injuries.”

From the research of famous running coach Jack Daniels at the 1984 Olympics, we now know that elite long distance runners at race speed almost always have a cadence of at least 180spm. We also see that the average recreational runner has a cadence of 150-170spm, with overstriders typically running with a cadence of less than 160spm.

Though overstriding is often accompanied by a heelstrike, it is important to remember that it is also sometimes seen with a midfoot or forefoot strike. Equally as relevant is the fact that although an initial contact closer to the body is commonly made with midfoot or forefoot strike, there are runners who manage it with a heelstrike (including Olympic silver medallist & New York City Marathon winner Meb Keflezighi).

The natural conclusion is that maybe less emphasis should be placed on worrying about what part of the foot touches the ground first and more on how close the front foot lands to underneath the hips.

Cadence Testing

If we accept the evidence that a cadence of less than 160spm is associated with increased risk of injury and that the majority (if not all) of elite athletes have a cadence of at least 180spm, being aware of our cadence kind of makes sense. If it is less than 160spm, an increase of 5-10% may well be an important factor in reducing injury. Even if it is over 160spm, increasing it by 5-10% may be a valuable tool (along with strength conditioning, dynamic flexibility, etc.) to help us move closer to the performance levels of elite athletes. As long as the changes are gradual and we listen to our bodies, it certainly seems worthwhile trying.

At one of the Brighton Marathon Expo’s a few years back (2013 to be precise), I had the opportunity to test the cadence of over 50 long distance runners of all levels. (In the feature photo above the introduction is the ever smiling face of Scott Goodwin, creator of Bosh Running Group ). My aim was simply to introduce them and their non-competing colleagues to the concept of cadence, so the only instruments I used were a mini foot pod (clipped onto the shoe laces) that measured and sent speed, distance and cadence information to an iPad, and a Sprintex slat-belt treadmill (designed to mimic natural ground reaction forces better than conventional belt-driven treadmills).

As stated above, the purpose was not to produce a double blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial (the list of design and conduct flaws is probably longer than the treadmill was). I did nevertheless make it clear to the runners that in order to give them helpful feedback it was vital they performed the test using their natural running form.

Only a small percentage of the runners had any preconceptions of cadence, and results for anybody whose cadence seemed irregular and/or non sustainable have not been included in the data presented in the table.

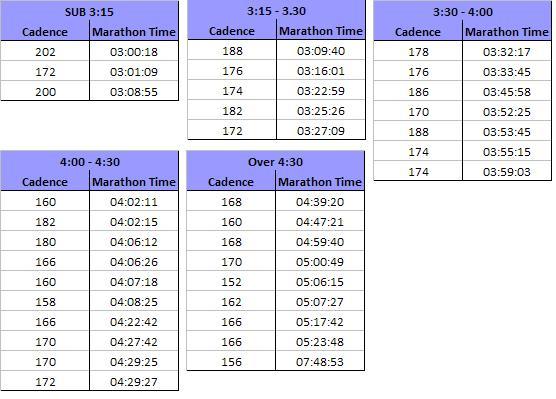

Of the 53 runners I tested, 34 went on to finish the Brighton Marathon, giving me the opportunity to compare their cadence with their finishing time. All participants wore trainers and, following a brief warm up at their chosen comfortable pace (7km/hr – 10.5km/hr), had their cadence recorded during a 10 second run at their chosen race pace (9.5km/hr to 14km/hr).

What do the results tell us?

As far as a trial goes, yes, this test had more holes than Swiss cheese. However, it does seem clear from the results above that as overall race time increases, cadence tends to decrease.

The two participants with a cadence of over 190spm both managed sub 3:10 race times. I wonder what the 172spm runner with a time of 3:01:09 could achieve if he managed to increase his cadence by 10%? For runners who exhibited a high cadence but slow race time, maybe this is evidence that they need to focus more on other aspects of running fitness, particualrly training habits and strength.

It would have been interesting to have recorded the level of injury that participants said they had suffered during training as there were multiple occasions where runners plagued with repeated injury showed a lower cadence than others who, though slower runners than their colleagues, had managed to get to race day injury free. Correlation not causation, but interesting nevertheless.

One runner who sticks out in my mind was a 59 year old grandmother who in just a year had come from never having run in her life to doing her first marathon. With no coaching whatsoever, her natural cadence at race pace was 170spm. She suffered no injuries in preparation for the marathon and happily completed it in a time of 5:00:49. Coincidence? Maybe. But definitely food for thought!

If this article has encouraged you to explore your own cadence for different running speeds (a warm up pace will typically involve a slower cadence than a marathon race pace, just as the cadence used in a sprint will tend to be higher still), make sure you use progressive increases in cadence (only 5% at a time). Who knows, it may be just the key to taking you out of an injury cycle or to a new personal best.

Related Posts

Five Best Ways For Runners To Warm Up

Want to know the five best ways for runners to warm up? What does the evidence say about Static stretching? How about Dynamic Stretching? What’s Dynamic Mobility? Prepare for surprises!

Hill Sprints for Novice Runners

For those relatively new to regular running, the notion of introducing maximal effort hill sprints is often met with concern over the possibility of over-training and encouraging injury. And yet, including one or two weekly hill sprint sessions into your training may well be safer than just knocking out long distances on flat ground.

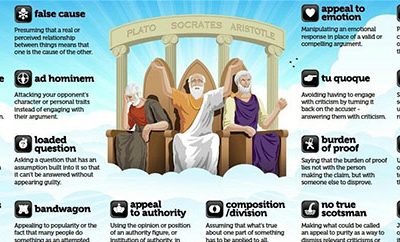

Natural Equals Good – Logical Fallacy

A logical fallacy is something used in discussion / argument / marketing that sounds supportive but is actually based on a misassumption. For example, assuming something /someone must be good because it’s been around for many years is called an ‘appeal to antiquity’. They are worth recognising as soft tissue discussions are full of them.

0 Comments