www.runchatlive.com

“Putting Evidence Back Into

Running Injury and Performance”

Do The Words We Use Heal Or Harm? – Guest Blog by Mike Stewart

Mike Stewart is a physiotherapist, researcher and university lecturer with over twenty years experience of helping people to overcome pain. With an MSc in Education and Physiotherapy, his published work has received international praise from the leading names in neuroscience. His ‘Know Pain Courses‘ have been taught in 17 countries and provide clinicians around the world with practical pain education skills. Having hosted & attended myself, I whole heartedly recommend them. The practical applications and methods they present can be taken into your clinic and applied immediately with your patients. Enjoy this guest blog by Mike Stewart and be sure to check out the knowpain.co.uk website.

Malaligned and overpronated:

Do the words we use heal or harm?

Mike Stewart

MCSP SRP BSc (Hons) MSc PG Cert (Clin Ed).

The roles and responsibilities of contemporary, evidence-based podiatrists are multifaceted and complex. As clinicians, we play a pivotal role in the lives of people in vulnerable, distressing situations. Which school of thought do we follow? Which outcome measure do we choose? What advice should we offer? Which words should we use?

The split-second clinical decisions we make can have a lasting impact. Both for the better and for the worse. What we say or don’t say is as important as what we do or don’t do. In a speech to The Royal College of Surgeons in 1923, the author Rudyard Kipling suggested that, “Words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind.” The words we choose can either contain the capacity to heal, or have the potential to cause devastating and lasting harm (Biro, 2010). Like drugs, words have an ability to change the way another person thinks and feels. Words are capable of corrupting thoughts, generating emotions and creating actions that lead towards behaviour change. Words can either make or break a positive clinical outcome (Darlow et al, 2013). This article aims to address the powerful, yet often concealed impact that language has in everyday podiatry consultations. To fully appreciate the implicit power that our words have, we must first reframe how we view pain. Our understanding of pain has fundamentally changed. Pain was viewed as a purely sensory experience, that was produced by the body and directly related to damage and harm. However, a substantial and growing evidence base within pain science has led to a more comprehensive, understanding with pain now regarded as a complex, idiosyncratic experience of distress that is produced by the brain as a response to perceived threat (Moseley, 2003).

Eccleston and Crombez (2007, p.233) argue that, “Pain is an ideal habitat for worry to flourish.” Without such a reconceptualisation, podiatrists may remain unaware of the potential harm their words may contain. As a result, they may continue to unknowingly fertilise pain’s vulnerable ground. Something that only takes a few seconds to say, and which means very little to you as a clinician, has the implicit ability to threaten somebody for a lifetime. In this sense, words are like toothpaste. Once they are out of the tube, they are impossible to put back in again. Learning to accept this, and seeking to develop practical strategies to clean up the complex mess that endures are crucial, unremitting healthcare obligations.

The case study in Table 1 below shows excerpts of dialogue from a consultation. Unspoken thoughts and beliefs are shown within parentheses.

A substantial evidence base shows healthcare communication to be predominately clinician led and paternalistic with patients left feeling disengaged with their worries and beliefs remaining unheard and unchallenged (Dierckx et al, 2013). A hierarchical structure exists where the patient takes a subordinate role (Sharon et al, 2015). This highlights a central dilemma within healthcare communication as the solutions to peoples’ problems are frequently found within their words and thoughts, not the clinician’s (Schwarzer, 2014).

Rather than talking and pouring in our clinical knowledge through words which may either confirm a person’s darkest fears or, as is the situation within the case study, igniting a previously unconsidered concern such as ‘degenerative’, ‘malaligned’ or ‘overpronated’, we must learn to listen more and talk less. Although this may sound simplistic, and some clinicians may feel that they already do this, the literature indicates that these skills are frequently assumed within practice (Bolton, 2010, Hinchliff, 2004). Briggs, Carr & Whittaker (2011) found that, in many healthcare disciplines, educational skill development accounted for less than 1% of undergraduate programme hours within the United Kingdom.

Through listening, drawing out and guiding, the therapist can begin to develop a better understanding whilst enabling a more optimistic, solution focused approach to overcoming problems. As Socrates reminds us, “To find yourself, you must think for yourself.” In order to empower people, clinicians must first be prepared to lose their power. Much of this power is held within our clinical words and knowledge. Knowledge comes with a curse. The more comfortable we become with what we know and the words we use to describe what we know, the more we forget that other people do not know what we do, and that they may attach an alternative, more threatening meaning to the words we use (Pinker, 2014).

The case study also highlights how our cognitive biases may distort reality. We construct a subjective social reality that is based upon our perception of sensory input (Fox, 2012). The therapist recognises the patient’s misinterpretation of

“degenerative changes” as “knackered” and attempts to minimise the harm through saying “wear and tear.” However, without realising the hidden impact, the therapist has unwittingly confirmed the patient’s belief that standing at work has led to a “worn out” foot. This, in turn, reinforces the patient’s pain behavior. Barker et al (2009) discovered patients often misinterpret medical terminology with “wear and tear” being perceived as “something is rotting away.” This finding was supported by Padfield et al (2010) who asked participants to display their perceptions of pain by creating photographic images to represent their beliefs. Wear and tear was depicted as of rotten, unhealthy fruit.

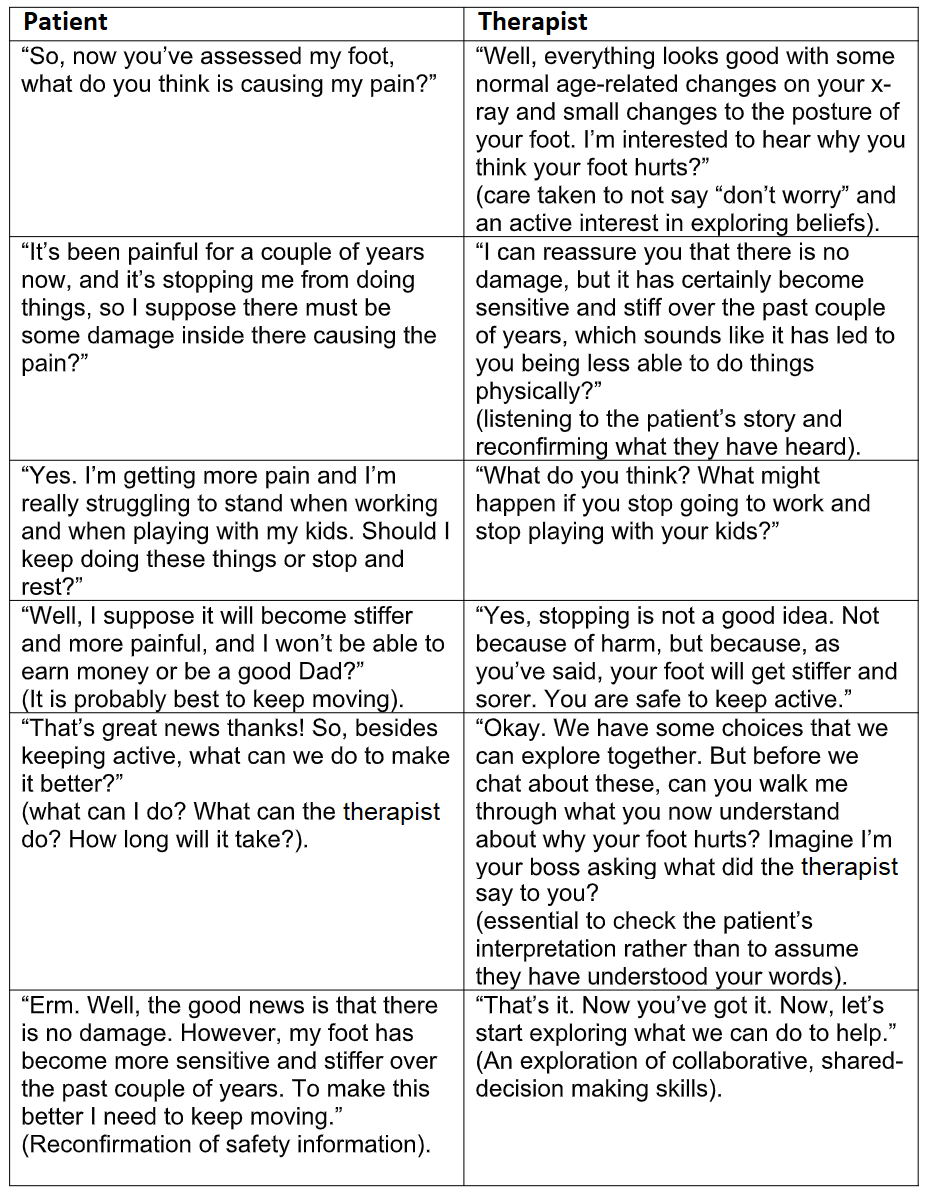

Consequently, following careful consideration of the evidence and an increased awareness of the issues raised, let us now contemplate in Table 2 how the case study dialogue may differ.

Take Home Messages

- Pain is produced by the brain as a response to perceived threat.

- The words podiatrists use can either heal or hurt by reducing or amplifying the extent of any perceived threat.

- Patients frequently feel disengaged as healthcare communication is often

clinician led and paternalistic. - Listen, find out what people need and then guide them.

References

- Barker, K, Reid, M, Minns Lowe, C (2009) Divided by a lack of common language? A

qualitative study exploring the use of language by health professionals treating back

pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 10. 123. - Bolton, G. (2010). Reflective Practice, Writing and Professional Development. 3 rd

edition. London. Sage Publications. - Briggs, E, Carr, E, Whittaker, M. (2011). Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for

healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Pain. 15 (8)

789-795. - Darlow, B, Dowell, A, Baxter, G, Mathieson, F, Perry, M, Dean, S. (2013). The

enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. The Annals of

Family Medicine. 11 (6) 527-34. - Dierckx, K, Devugele, M, Roosen, P, Devisch, I. (2013). Implementation of shared decision making in physical therapy: observed level of involvement and patient preference. Physical Therapy. (10) 1321-30.

- Eccleston, C, Crombez, G. (2007). Worry and chronic pain: A misdirected problem solving model. Pain. 132 (3) 233-236.

- Fox, E. (2012). Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain. The new science of optimism & pessimism. London. William Heinemann Publishing. ISBN 9780434020171.

- Hinchliff, S. (2004). The practitioner as teacher 3 rd edition. London. Churchill Livingstone.

- Moseley, G.L. (2003). A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy. 8 (3) 130-140.

- Padfield, D., Janmohamed, F., Zakrzewska, J. M., Pither, C. and Hurwitz, B. (2010) ‘A slippery surface: Can photographic images of pain improve communication in pain consultations?’, International Journal of Surgery, 8, 2:144-150.

- Pinker, S. (2014). The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21 st Century. New York. NY: Penguin.

- Schwarzer, R (2014) Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. Routledge. London.

- Sharon, L, Delany, T, Sweet, L, Battersby, M, Skinner, T. (2015). Barriers and enablers to good communication and information-sharing practices in care planning for chronic condition management. Journal of Primary Health. 21 (1) 84-89.

0 Comments